Wake up Australia, we have a debt problem

Fast forward ten years, we are replaying the start of their story. Thousands of Aussie borrowers are facing a repayment increase on their mortgages in the next 18-24 months. Most have no idea. Many won’t be able to afford it.

Australia, we have a debt problem.

This article puts a spotlight on the origins of our debt problem and explains how we got here. For background, in this earlier article, we explained how Australian interest only loan contracts work and how these loans will have a repayment increases in coming years.

How did Australia get into a debt problem?

1. Interest rate reductions & and a failure in lending market oversight (2011-2015)

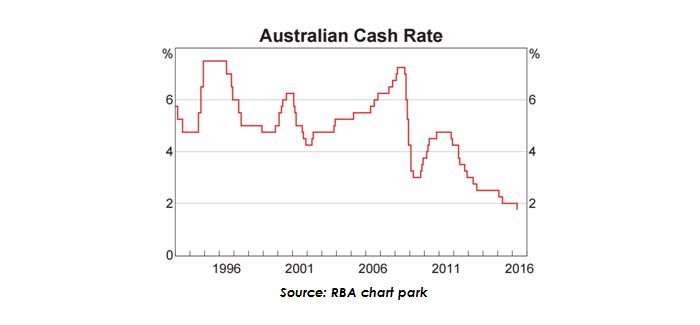

The origins of our debt problem begin with interest rate reductions following the end of the mining boom. Naturally, the cash rate reduction incentivised Australian’s to take on more debt.

To safeguard against poor lending practices, APRA reliedon lenders to stress test whether borrowers could afford repayments if interest rates rose by at least 2%. This stress testing would ensure that borrowers could afford future repayment increases.

However, lenders ignored this key pillar of lending regulation. They only applied this buffer to new debt, not to debt that customers held with other banks. This loophole effectively allowed some borrowers to avoid ‘stress testing’ when obtaining a loan.

2. Big ramp up in lending & interest only lending (2012-2016)

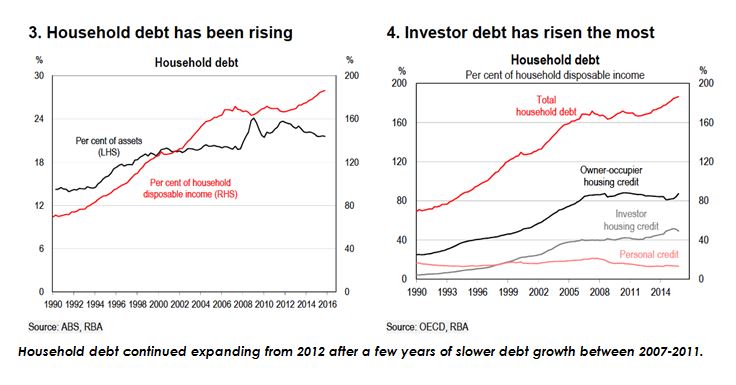

With rates at record lows, and no one adequately supervising the banks, Australia’s household debt continued to grow between 2012-2015.

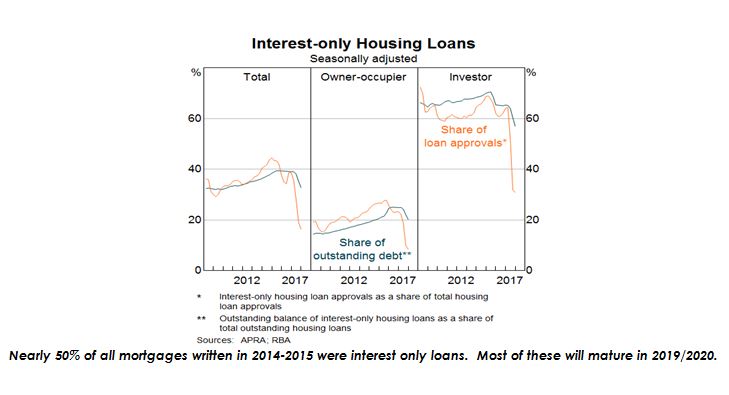

House prices begun rising & interest only loans had become increasingly popular. These are loans that borrowers don’t have to pay down for the first 5 years of their loan term. Thereafter, these loans have their repayments increase as they move back to principle and interest terms. On a $500,000 loan size, the repayment increase after 5 years is roughly $900 per month.

3. A crackdown on lending policies & Interest Only lending (2015 &2017)

Eventually, regulators started to get concerned about the rapid growth in residential mortgages&looked at how lenders were applying their lending assessments.

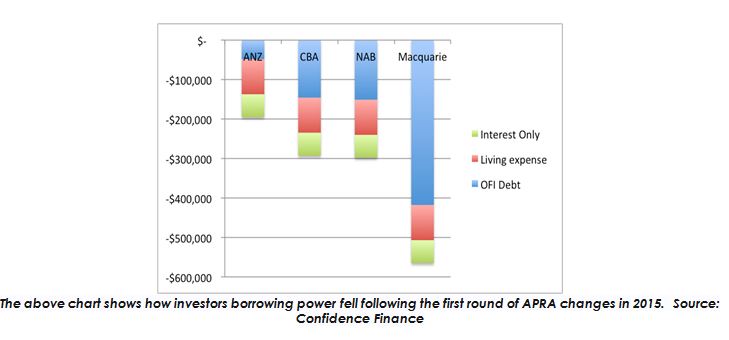

APRA soon realised lenders only stress tested some debts, assumed borrowers had unrealistically low living expenses, had no restrictions on interest only lending& didn’t advise borrowers that repayments increased in future years when interest only periods expire.

What followed was a massive reduction in borrowing capacities and restrictions on interest only loans as lenders applied more robust buffers in their affordability calculations. Borrowers would also be required to meet the new lending rules to have their interest only terms extended.

4. Interest only periods expire & the repayment crunch begins (2018-2020)

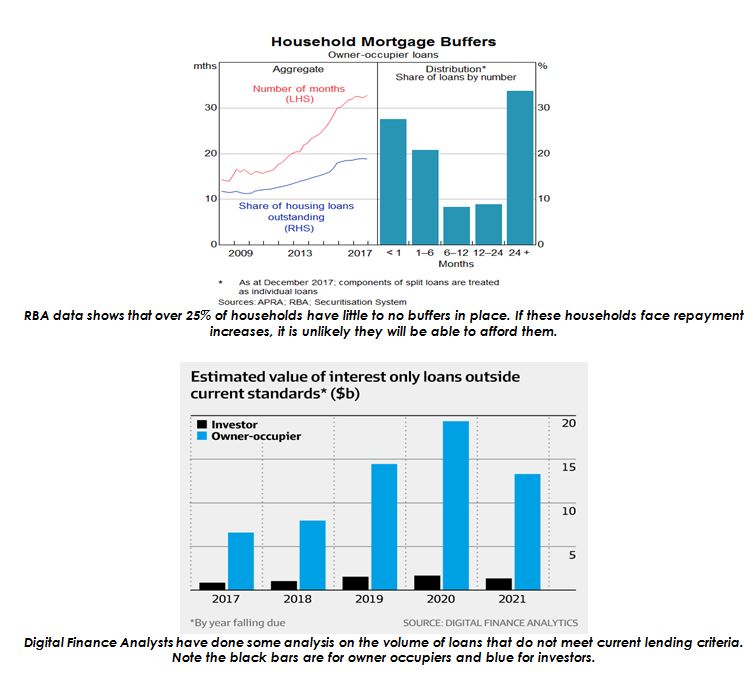

The glut of interest only lending that was approved under poor lending practices has a potential cost. Borrowers that got those loans will be facing higher repayments when their IO periods expire. Many will not pass the new higher lending standards. Furthermore, over 25% of households have less than 1 months savings available to them to absorb repayment increases.

What options do borrowers have?

Borrowers on interest only loans that mature will fall into one of the following four categories, from best to worst;

- Make the additional repayments when the loan converts to principle and interest repayments; borrowers can simply adjust their situation and make the additional repayments. Many borrowers have already begun preparing for changes and done this already.

- Refinance their loan with a mainstream lender and extend their interest only term; this is only available to borrowers who can pass current eligibility criteria. As a guide, for every $1million in debt borrowers have, they will need an additional $40k in household income to support the same level of debt today vs 3 years ago. With little to no wage growth, many may no longer qualify.

- Refinance their loan with a non-bank lender; for those who are desperate to maintain their interest only period but fail servicing with mainstream lenders, they can go to the non-bank lenders to secure a new IO period for another 5 years. These lenders have less restrictive lending criteria, but interest rates are usually 0.50-1% higher.

- Sell; when all else fails, borrowers can sell their properties/investments. This is unlikely to lead to large scale losses for lenders or borrowers, as house prices have grown rapidly and data shows Aussie’s are on relatively low LVRs.

What should the regulators do about it?

Firstly, the regulators need to understand the size of the problem.This month the RBA and the IMF both dressed over Australia’s debt, looking at current financial stress indicators to play down any issues. Financial stability experts know this analysis is weak, as measures of financial stress lagwell behind origination problems. Furthermore, many borrowers are completely unaware of their repayments rising (hence aren’t stressing about them!).

What the RBA, APRA & ASIC need to be doing is working out:

- When borrowers interest only terms expire

- Which of the four baskets above do these borrowers fall into

Only then can the size of the problem be properly quantified.

If this analysis reveals a big enough problem, regulators will need to devise a way to soften the landing. Here is a draft five-point plan to manage the market impacts:

- Allow investment interest only loans to be extended without reassessing borrowers to new serviceability criteria. This pushes the problem down the road and spreads the timing of interest only expiries.

- Allow lenders to re-issue 30-year loan term for borrowers whose interest only terms expire. This will help lower the repayment crunchas repayments will be over 30 years rather than 25.

- Promote or incentivise non-banks to continue to provide solutions. Competitive pressure can help alleviate price gouging from smaller lenders.

- Allow lenders case by case extensions to interest only periods where required.

- As a last resort, consider further reductions in the cash rate or delays to upward movements to help manage the broader risk to the economy.

How likely is a ‘soft landing’?

Australian regulators have been facing a delicate balancing act managing the economy post mining boom. At this point in the economic cycle, the regulators job is to orchestrate a soft landing.

While the start of our story is like America in 07, the way this story unfolds will likely be far less dramatic.

High household debt is a threat to the economy and requires robust monitoring and management. To date, regulators have failed to appropriately acknowledge the size of the current debt problem.

Nonetheless, they have the tools in their locker & a proven track-record of success to suggest that Australia’s debt problem will end with a soft landing.

About the author:

Redom Syed is the Founder of Confidence Finance. Redom has been recognized by MPA magazine the Youngest Top 100 Broker’s in Australia after settling over $150 million in lending. Prior to becoming a finance broker, Redom worked as a Macro-Economist at Federal Treasury. Here he became a published author on the design of the International Financial System and spent 3 years working on financial market regulation.